Long read – 11 minutes read time.

John Hudson is a Professor of Social Policy & Academic Director of the University of York’s policy engagement unit The York Policy Engine. He is one of the academic leads for Y-PERN’s York and North Yorkshire sub-region.

From Practice to Theory

The Yorkshire and Humber Policy Engagement Research Network (Y-PERN) was rooted in a ‘network of networks’ approach from the outset. Our bid to the Research England Development Fund proposed a “distinctively network-based model of policy engagement” that would both exploit and deepen pre-existing regional infrastructure “to deliver a novel network-based approach to […] academic policy engagement and research”.

Arguably it was a model rooted more in practice than theory. Rather than citing a raft of conceptual papers, the bid’s credentials rested on the success of prior projects rooted in this approach. Yet, while conceptual debates did not explicitly feature in Y-PERN’s funding bid, social science debates about networks had informed thinking. As the project has evolved, the question of how far key ideas in these debates might aid reflection on Y-PERN’s ‘network of networks’ model is one we have periodically returned to.

One reason for avoiding this question is the huge number of ‘network’ debates across the social sciences makes it difficult to know where to start. As a recent paper by Oliver and Faul underlined there is a “significant variation in how researchers use and interpret terms like network, tie, relationship, broker and link – probably because while they all have discipline-specific meanings as technical terms, they also have general meanings”.

Such confusions persist even within applied policy fields such as public administration where Lecy et al noted “The most cited articles […] often use similar terms (such as ’policy network’) to describe very different types of networks” and where, as Isett et al highlighted, “The word ‘network’ is used loosely throughout the literature and can refer to many different things”.

Tackling the question thoroughly in a blog post is, therefore, impossible. But, as a first step, we can distill some themes from a selection of prominent debates and use them to aid reflection on how Y-PERN’s ‘network of networks’ model has developed and where it might go next.

Networks vs Hierarchies

In his classic exploration of the ‘network society’ sociologist Manuel Castells conceptualised networks as a flexible form of social organisation which comprise of “a set of interconnected nodes”. He contrasted this with other forms of social organisation such as “centralised hierarchies” that feature a central authority. Indeed, Castells saw this as key to understanding networks as an organisational form, arguing “by definition, a network has no centre”, and that networks “de-centre performance and share decision-making”.

Castells’ saw this dispersal of authority as fueling dynamism as nodes are connected or disconnected based on the value they add to a network’s goals at any given moment, arguing networks work “on a binary logic: inclusion/exclusion”. He saw such flux as an essentially automatic process as flows in a network switch to the most useful nodes, arguing “If a node in the network ceases to perform a useful function it is phased out from the network, and the network rearranges itself – as cells do in biological processes”. From such a perspective, even the most powerful nodes “are not centres, but switchers, following a networking logic rather than a command logic, in their function vis-à-vis the overall structure”.

Castells’ ideas provide interesting prompts for reflection on Y-PERN’s approach. Is a successful ‘network of networks’ approach to academic policy engagement one that establishes enduring connections between, say, key policymakers inside a combined authority and a specific research specialism in a particular university or one that facilitates rapid switching of connections between different policymakers, universities and research specialisms as immediate needs shift?

Does it require an organisational form based around strong central control of project tasks and resources or one that devolves resources to multiple nodes that can switch their focus at speed? Should areas for collaboration between policymakers and researchers be clearly scoped at the outset or be allowed to emerge as the project unfolds?

These are central dilemmas the Y-PERN project has grappled with as it has progressed. The fluidity of operation implied by Castells’ networking logic has been present from the outset because Y-PERN was premised on a ‘demand led’ model whereby policy stakeholders drive the flow of expertise from universities based on their evidence needs. In this sense, nodes of connection have risen and fallen as policy agendas and policymaker evidence needs have evolved. Indeed, even some of Y-PERN’s initially planned core outputs were deprioritised when it became clear other activities would offer greater value to the network. Moreover, while no project in receipt of significant public funding can proceed without the level of central oversight required to ensure resources are appropriately and effectively allocated, Y-PERN was established with a federal structure that fused a central co-ordinating function with ‘devolved’ teams in sub-regions empowered to develop their own approaches and with ringfenced resources to support this.

Networks, Relations and Social Capital

But Castells’ depiction of connections in informational networks as largely transactional and value free – networks “can equally kill or kiss: nothing personal” as he put it – does not capture dominant thinking about the role of relationship building in effective academic policy engagement. Indeed, CAPE’s ‘what works’ review argued strong stakeholder engagement is vital, “takes time and effort, and needs foregrounding […] sustaining over time, not operating as an isolated one-off”.

Does this suggest the development of trusted connections between individuals is key to a successful ‘network of networks’ model? Oliver and Faul noted “Many commentators agree that evidence use – whether we call it knowledge exchange, research impact, or some other variant – is essentially a relational process, and takes place in social settings” and, in asking “What would it mean to take this relational aspect of evidence use seriously?” argued “Network analysis offers an unparalleled window onto the relations that flourish – and those that do not – in the evidence-policy ecosystem we study or work in”.

Cvitanovic et al used social network analysis to explore the impact of knowledge brokerage roles in connecting policymakers and researchers in an Australian climate science organisation and found brokerage played an important role in bridging and bonding network connections.

In the Y-PERN model, a key innovation has been the appointment of around a dozen Policy Fellows whose roles fuse policy research and knowledge exchange functions and who work within their sub-regions to broker connections between local policy stakeholders and researchers.

Ideas around social capital common in social network analysis may be of particular use in unpacking the role of Policy Fellows in the ‘network of networks’ model. Y-PERN was designed to bring together existing networks operating in largely separate areas – e.g. policymakers in local authorities in one set of networks, university researchers in another. Y-PERN’s Policy Fellows might be viewed as a key example of linking capital in the ‘network of networks’ model, their work in building trust and understanding building bridging capital that has helped strengthen ties between policymakers’ networks and researcher networks in the region.

Image – Y-PERN Policy Fellows

Y-PERN has implemented multiple variations of the Policy Fellow role as it has tested its approach, including roles embedded in policy organisations, in universities and in a mix of the two. Viewed from a relational perspective, a question we might ask as Y-PERN moves to its next phase is whether specific versions and features of the Policy Fellow role have been more effective in developing bridging capital.

Policy Networks and Power

However, taking a relational approach seriously, particularly in a context where political interests come to the fore, means acknowledging that power is a fundamental feature of interactions.

Numerous models of policy network analysis have explored this terrain, with the Marsh and Rhodes model the most prominent in the UK. From this perspective, policy networks are an autonomous and self-organising collection of actors with shared but competing interests bound together by resource dependencies. In this view, the positions of actors in a network are shaped by the resources they bring to these interdependencies, with networks typically featuring a core (comprising stronger nodes) and a periphery (comprising weaker nodes), with the latter often seen as outsider groups.

Reflecting on these questions of power and networks, it has mattered that Y-PERN’s ‘network of network’ approach built on two key pre-existing networks representing key institutions in the region – Yorkshire Universities and Yorkshire and Humber Councils – and that those networks feed directly into Y-PERN’s own governance structures. This has created powerful institutional buy-in from those leading existing networks and means Y-PERN differs fundamentally in its status and standing from a policy engagement team attached to a large research project for example.

But policy network theory also points to some tightropes the Y-PERN ‘network of networks’ model has had to walk as it has developed. Marsh and Rhodes argued policy networks centred on a tightly connected group of powerful actors often reinforce a status quo that serves the interests of insider groups. As Y-PERN connects strong ‘insider’ institutions in the region this is a risk we have needed to be mindful of, doubly so given central government direction of regional resources and agendas often serves to prioritise a narrow range of (primarily economic growth and business focused) issues and perspectives. The breadth of Y-PERN’s work has helped address this dilemma, covering a wide range of policy areas such as regional skills needs, good growth, the barriers to female entrepreneurship, childcare policy, anti-poverty policy, and flood and climate change resilience.

Significantly, in some of these instances, Y-PERN activity has aimed to deliberately amplify the voices of groups usually classified as being at the periphery of policy networks. The Yorkshire Policy Innovation Partnership (YPIP) project that builds on the Y-PERN network aims to do so explicitly, including through the creation of a Community Panel that will connect policymakers and citizens with direct experience of disadvantage, marginalisation or isolation and through an open-call ‘Communities Innovating Yorkshire Fund’ (CIFY) that provides grants to organisations for community-led inclusive and sustainable growth.

However, this raises the question of how Y-PERN should use an understanding of power in policy networks to inform its ‘network of networks’ model.

Network Management

The ‘governance club’ branch of policy network theory offered arguments that are useful for reflection here. Their work outlined contrasting approaches to ‘network management’, ranging from ‘game management’ focused on better handling of interactions between core network members through to ‘network structuring’ focused on reshaping the nature and membership of the core network itself. They suggested the latter might involve ‘network activation strategies’ that bring peripheral, or even latent, nodes more firmly into the activity of the core network; CIFY might be seen as rooted in exactly such an approach.

The contrast between perspective on the dynamics of networks in the ‘governance club’ and the fluid ‘kiss or kill’ model driven by irresistible network flows in Castells’ informational networks is stark.

But contrasting the two hints at a key question: does a successful ‘network of network approach’ work with the dominant flows of power in networks or does it look to restructure networks by, for instance, bringing issues and actors at the periphery of network activity closer to the core?

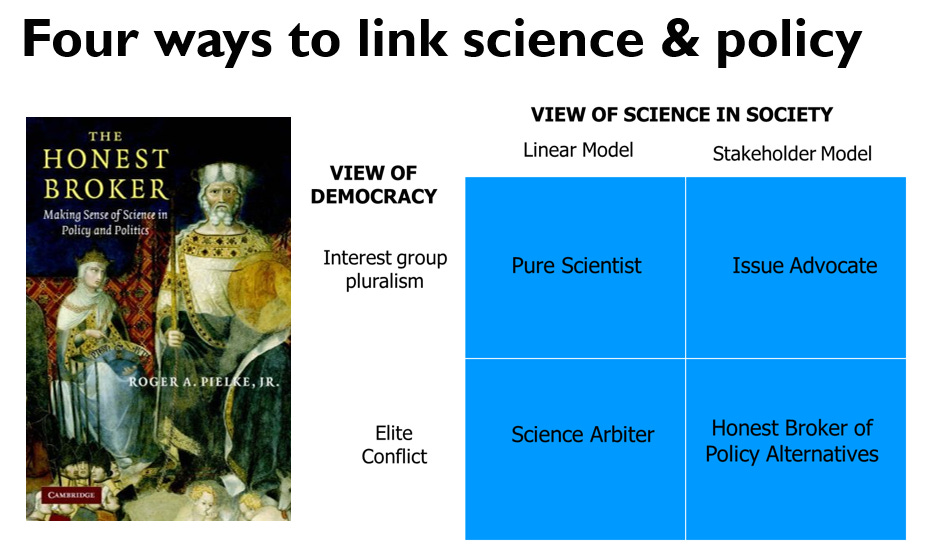

Here there are difficult questions that lack simple answers that have featured in long-running debates about the role scientific evidence should play policymaking. These were neatly captured in Pielke’s classic study that outlined different stylised ideal types of the role scientists might play here – such as ‘scientific arbiter’ (answering factual questions, but not advising what should be done) or ‘issue advocate’ (making the case for policy changes suggested by research findings) – each reflecting different value judgements on the appropriate role.

Image – Roger Pielke’s Four idealized roles of science in policy and politics

From Theory (Back) to Practice

In their reflections on ‘networks and network analysis in evidence, policy and practice’ Oliver and Faul called for “more clarity about the use of network terms and approaches”, asking “what analytical work does ‘network’ do in a study? What theory or perspective does it imply?”. As Y-PERN Phase 1 moves towards its conclusion and we look to refine our approach in a Y-PERN Phase 2, delving into conceptual debates from ‘network theory’ will help us address these questions and, in turn, reflect on what we mean by a ‘network of networks’ approach, how we hope it will inform how partners work together, and the value – or even values – the approach brings to policymaking in the region.

Y-PERN would like to thank John for his reflections on Y-PERN’s network of networks approach.